In 2013, in the Italian town of Chiavari near Genoa, architects Nicola Spinetto and Daniele Manetti transformed an unkempt plot of land with a sharp slope into a wonderful multi-tiered garden. We tell you how they did it.

Architect Nicola Spinetto proposed an ingenious solution to a fairly common problem - the need to develop a site on a steep slope.

In collaboration with Daniel Manetti, he managed to transform a neglected garden in a private house on the Italian coast of the Ligurian Sea beyond recognition and turn it into a multi-tiered amphitheater garden with a dining area and a country kitchen.

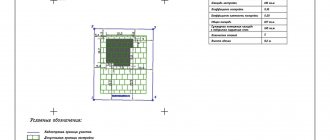

Project details

Garden area – 175 sq.m. In this fairly compact space, the designers placed a three-tier terrace and a dining area with a table and chairs. The covered summer kitchen took up another 12 sq.m.

Terrace: room in the garden, garden in the room

Mastering a small space requires a lot of imagination and the ability to resist the temptation to own everything. The design of a small garden should be simple and minimalistic. On the terrace, as in the house, everything should be well planned, since in a small space it is easy to create unnecessary chaos and a feeling of overload.

The need for planning and non-purpose space creates some restrictions - which can be seen as advantages - because when everything is concentrated in a narrow space, organized and under constant control, it gives a feeling of privacy and security.

Garden path-deck

An interesting detail of the project - the garden path - is made of boards in the form of a deck. It leads from the house to the summer kitchen, expanding into the dining area. The sides of the terrace and the kitchen are lined with the same material as the deck - Douglas fir (pseudo-hemlock).

According to Nicola Spinetto, the boards were deliberately left untreated so that the wood, under the influence of salt-saturated Mediterranean air and the hot sun, would eventually acquire an interesting texture and a characteristic grayish tint.

Slope strengthening

As can be clearly seen from the photographs, the house is located in a mountainous area, so the slope of the site was quite sharp. And in order to even out the relief, the designers “cut” the hill, arranging a three-level terrace on it.

Considering that several mature trees with a powerful root system grew on the slope, the tiers needed to be reliably strengthened. At first glance, it may seem that a wooden “fence” holds this entire volume of land, but in fact, the wood here is used only as cladding, and the role of support is performed by concrete blocks.

A nice bonus is that mini-benches are built into the terrace structures.

Features of viticulture on the slopes

FEATURES OF VITIFICATION ON THE SLOPE

Based on the length of the section from the watershed to the gully, slopes are usually divided into short (up to 100 m), medium (100-300 m) and long (over 300 m).

Based on the shape of the surface in a section perpendicular to the horizontal lines of the terrain, straight, concave, convex and stepped slopes are distinguished.

A concave slope is usually more fertile than a straight and especially convex one. On a stepped slope, fertile areas alternate with less fertile ones.

Mechanization of work on slopes in general and in vineyards in particular should not only ensure the creation of favorable conditions for plant growth at the lowest possible cost, but also counteract water erosion of soils. This problem is solved differentially depending on the steepness and length of the slope, the type of plantings and the system of their cultivation. The steepness of the slope is a determining indicator in the selection of energy resources, machines, tools and the method of their use.

Scientific research and the experience of collective and state farms have shown that in some conditions, on slopes of slight steepness (up to 6°), the viticulture system should not differ from the usual one. Tractors, machines and implements designed for working in lowland vineyards can be used here. With an increase in steepness, some changes in planting schemes and agricultural technology are necessary, as well as replenishment of the machine system with special equipment.

On steep slopes, viticulture needs radical restructuring. There must be engineering preparation of the territory; the mechanization of many operations requires the use of special machines.

The division of slopes into groups according to steepness in connection with the characteristics of viticulture and mechanization corresponds to the classification proposed by prof. P.V. Ivanov.

Group I. Gentle slopes up to 6° steep. In such areas, provided that the rows of the vineyard are located across the slope and, therefore, the soil is cultivated in this direction, the kinetic energy of water flowing along the surface of the field is, as a rule, insufficient to drag down soil particles lying on the surface or to disrupt the internal connections between soil particles ny monoliths.

Therefore, significant erosion processes are not observed here. Special research and testing of machines have shown that at such a steep slope, vineyard tractors and machines work satisfactorily. The quality of soil treatment when performing other operations to care for plantings does not differ from the treatment of vineyards on the plains.

Group I slopes are used for cultivating vigorously growing table and technical grape varieties. It is planted in row spacing of 2-3 m, the distance between bushes in rows is from 1 to 2 m.

Group II. Sloping slopes from 6 to 12°. With a significant length of slopes of such steepness, the kinetic energy of flowing water during intense precipitation can reach a critical value. Therefore, in such areas, simple anti-erosion measures should be used. When cultivating row crops, for example, in row-spacing, crevice, intermittent furrowing, formation of microlimans, etc. are practiced.

On grape plantations the need for such work arises less frequently. This is explained by the fact that the planting of grapes is preceded by deep (50-60 cm) plowing, as a result of which this area has a high moisture-absorbing capacity for a long time. Over the course of 3-4 years, a process of self-terracing takes place between the rows.

The presence of horizontal platforms between rows (microterraces) on slopes of such steepness reliably prevents water erosion.

The direction of fall of the slopes of group II is often variable, the terrain horizontals have a more pronounced curvilinear shape than on the slopes of group I.

To ensure the implementation of the main principle of mountain farming - tilling the soil across the slope, it is necessary to place rows of bushes, adhering to the horizontal lines of the terrain, that is, curvilinearly. This method is called contour. If the radii of the terrain contours are large enough, then the rows can be broken, their segments straight.

If we take into account the cross-country ability of tractor units, it is preferable that the blocks consist of straight sections, smoothly connected to each other. It has been established that the radius of curvature by which these curved segments are connected must be at least 15 m.

Quarters in the territories of group II are elongated along the main direction of the horizontal lines or have a trapezoidal shape. On their sides there are inter-block roads or turning lanes.

Mechanization of work on grape plantations on slopes of group II is associated with certain difficulties. Therefore, the equipment and technology used here need adjustments. The main feature is the sliding of tractors and machines connected to them downwards. As a result, the traction force of the tractor and the protective zone at the bottom row are reduced, maneuvering the unit becomes more difficult, and the risk of damage to the bushes increases.

These difficulties are most evident in the first years after planting, when self-terracing has not yet occurred. But when microterraces are formed between the rows, the working conditions approach flat ones.

However, when the unit leaves the road, which usually maintains the original slope of the terrain, negative factors again affect it. When the road steepness is more than 9a, the roll of vineyard tractors exceeds the permissible value. It is dangerous to work at this level.

The conditions of formation turnover also change significantly. When planting on slopes steeper than 8°, the layer has to be turned in one direction (down the slope), which significantly reduces labor productivity. Group II slopes are recommended for planting technical and table grape varieties.

In the process of self-terracing, the trunks of the bushes are covered with earth, making catarification difficult, creating a threat that the grafted vineyards will switch to their own roots. Consequently, it is better to plant them on slopes up to 8° steep, where the layer of accumulated soil is small. Rooted vineyards can be placed without prior terracing on slopes of greater steepness.

III group. Strongly sloping slopes from 12 to 18°. On such slopes, especially when they are plowed, erosion processes are very intense. To plant vineyards and other perennial crops on slopes steeper than 12°, terraces must be built.

In some farms, grapes are planted without terraces on steeper slopes. This should be approached with caution; this method does not guarantee against the danger of erosion and has little promise with regard to the mechanization of a number of labor-intensive operations. In addition to a good anti-erosion effect, terraces with a certain geometry and the correct road network system make it possible to mechanize the cultivation of vineyards to the same extent as on the plains.

The above-mentioned difficulties in operating machine-tractor units, especially when working on slopes of group III, greatly increase with increasing steepness, and on terraces, which are extended, almost horizontal areas, the units operate in approximately the same conditions of dynamic equilibrium as on the plains. The only problem is their turning on the roads. But this can be successfully overcome by proper design and construction of roads and turning lanes, the steepness of which should not exceed 8°. On the slopes of group III, technical grapes and less often table varieties are usually grown.

IV group. Steep slopes from 18 to 25″. The slopes of this group are developed by arranging terraces. The construction of terraces and road networks in such areas requires special earth-moving equipment. Geological and soil surveys must first be carried out with great care to eliminate the risk of landslides and destruction of these structures. On such terraces, low-growing, uncovered grapes of technical varieties are usually grown, producing high-quality wine materials.

V group. Slopes steeper than 25° or less steep, but very rugged. The development of slopes of this group with the existing level of technology requires large expenses for territory preparation and provides little economic effect.

The exception is certain mountainous regions in the Caucasus and Central Asia, where there is an acute shortage of areas suitable for agricultural use, and there are especially favorable conditions for growing citrus crops and grapes. Therefore, slopes with a steepness of more than 25° are used mainly for pine groves, walnut and forest plantations.

Sometimes on steep slopes grapes are grown by placing rows along the slope. This requires less cost for preparing areas and allows you to mechanize the care of plantings using rope traction tools. However, due to the high risk of erosion, such a viticulture system is permissible only in the presence of special soil conditions, for example, on rocky (slate) soils.

The division of sloping lands into groups, within which the viticulture system, agricultural technology and mechanization are approximately the same, facilitates the selection of existing and development of new machines for the mechanization of grape cultivation in these conditions.

It is known that the steepness of slopes has a great influence on the growing conditions of plants. With increasing steepness, the features of the microclimate of a given area become more pronounced, soil fertility and the thickness of the humus horizon decrease, the danger of erosion processes increases, the conditions for mechanization become more complicated, and the volume and complexity of preparatory work and engineering structures that ensure the possibility of economic use of these lands increases.

Depending on the specific soil and climatic conditions of the area, the steepness of the slope and the degree of ruggedness of the territory, industrial cultivation of vineyards on slopes is organized by two methods: without changing and with changing the microrelief of the area. The first method is used on slopes of groups I and II (up to a steepness of 12°). The preparation of such areas begins with uprooting trees, bushes, stumps, collecting large stones and filling ravines, gullies and holes.

Then, as on the plain, the planting is raised approximately along the horizontal contours of the terrain, with the difference, as noted, that with a steepness of more than 8° it is necessary to plow with the dump of the layer only down the slope.

After leveling the planting, the area is marked and seedlings are planted. Rows of plantings are placed along horizontal lines in straight segments, forming broken lines or contour rows smoothly curving along the entire length.

The angles between adjacent straight sections are no less than 150°, and the radii of curvature for contour plantings are no less than 15 m. The best solution is when the straightness of the rows is maintained throughout the entire cell, and the direction of the rows turns along the intercellular road. To fulfill this condition, cells are sometimes made in the shape of a trapezoid. This arrangement of rows can only be achieved in areas where the terrain is relatively calm. In this case, the inevitable slopes along the row should not exceed 3° over a length of up to 50 m. On very extended slopes, flow-regulating shrub forest belts are planted every 300-400 m. Planting patterns on non-terraced slopes differ little from those on the plain and, depending on the soil, biological characteristics and type of bush formation, the row spacing ranges from 2 to 3 m.

Since on slopes of group II, row spacing with a width of 2 m somewhat impedes the passage of tractor units, then on contour plantings with a steepness of more than 6°, the minimum row spacing should be 2.25 m. Due to the complexity of the terrain, blocks have to be made in an elongated shape, approaching a trapezoid with a smaller base in the top of the slope.

The length of the quarter is in the range of 600-1000 m. The width of inter-quarter roads is 7-8 m. In such conditions, it is not always advisable to divide the quarters into hundred-meter cells, as is done on flat plantations. In contour plantings, cells are sometimes up to 400 m long.

They strive to make the steepness of inter-block roads no more than 8° in order to reduce the risk of erosion and ensure the possibility of carrying out a number of transport operations. Unfortunately, in practice this requirement is not always met, and on plantations you can still find roads with a steepness of up to 10° or more. On such roads the tractor may overturn.

In some farms, slopes steeper than 12° are developed without terracing. Under certain conditions, for example, with a sharp increase in the steepness of a section, on a narrow strip that again turns into a surface of low steepness and length, it is necessary to allow a slightly greater steepness. But more often it happens when on very long slopes terracing must begin already at a steepness of 8-10° or other effective measures against erosion must be taken.

Attempts to plant grapes on steep slopes without terracing are associated with imperfect technology for building terraces and cultivating the soil and caring for plantings on terraces. Sometimes there is an underestimation of erosion danger.

Despite the high moisture-absorbing capacity of the site after planting, on long slopes with a steepness of more than 10-12°, the danger of erosion is very high. In the first year, when the soil is loose and poorly cohesive, a lot of humus is carried down from the site. In the next 2-3 years, when self-terracing has not yet finished and the soil has already become compacted, flow rates increase. The erosion danger increases even more.

As a result of the formation of terraces between the rows, in the third or fourth year after planting, the bush trunks are covered with soil. On slopes with a steepness of 14°, the trunks are filled up to 25–30 cm, and with a steepness of 16°, the height is 35–40 cm. Therefore, even if, during planting, the junction of the rootstock and scion is placed 10–12 cm above the soil level, the catarrh conditions will remain throughout the entire the life of the bushes is significantly hampered, and the labor costs for performing this operation increase sharply.

Some practitioners mistakenly believe that planting grapes without terraces on slopes with a steepness of 12-16° allows you to have more bushes per hectare. The fact is that when cultivating grapes without terraces on slopes of more than 12°, the row spacing has to be increased to 3 m in order to use 3-ton class tractors for cultivating the soil.

It is possible to use the T-54V vineyard tractor here only 3-4 years after self-terracing is completed. If, at the same steepness, plantation terraces 4 m wide are plowed and grapes are planted on them according to the pattern adopted on terraces (row spacing is 2.25 m, edge width is 0.9-1 m), then due to the short length and height of the slopes, the number of bushes per 1 hectare of slope turns out to be greater when terracing. Therefore, the cost of preparing a site for planting grapes, per 100 bushes, on terraces built using the plantation method is less.

When caring for the soil on terraces, the protective zone on the row-spacing side and part of the inter-bush space can be treated with equipment used on plains (PRVN-72000 device). A machine has also been created for processing edges.

On a non-terraced slope with a steepness of more than 10°, the protective zone and the soil between the bushes have to be processed manually. At a steepness of 14° this area is 36%, and at a steepness of 16°—48%. Most of it is a slope resulting from self-terracing. Since mechanization of this work will only be possible in the distant future, farms that intend to create such plantings must be prepared to cultivate more than a third of the area by hand for many years.

The same situation applies to covering vineyards for the winter and opening them in the spring. If on terraces there is a prospect of at least partial mechanization of these extremely labor-intensive processes, then on terraced slopes with a steepness of more than 10°, an attempt to cover the grapes by forming a bank of earth above the vine laid on the soil surface will cause it to spill into the underlying row spacing.

The costs of labor and money to prepare a site for planting grapes without terraces and on terraces with a slope of 10-16° differ little. In both cases, soil and geological surveys are necessary. In this case, it is necessary to carefully design the placement of plantings, the general organization of the territory and build a road network. And the construction of terraces with a plantation plow with simple accessories is no more expensive than continuous plantation plowing, turning the layer only down the slope.

One of the determining conditions for the steepness limit is an assessment of the soil conditions for the growth of this crop. It is known that during the construction of stepped terraces, due to the imperfection of the technology used, a certain part of the fertile layer is transferred from the excavation part of the canvas to the embankment and to the slope. However, this provision does not apply to the plantation method of terracing, especially on slopes up to 16° steep.

When constructing terraces with a planting plow, the skimmer removes the top fertile layer and dumps it at the bottom of the furrow. The surface plowed under the strip terrace turns out to have less fertile soil. With a slope steepness of 12–16°, the height of the excavation slope is 15–30 cm. When, as a result of the final design of the geometry of the bed, part of the soil (up to 30 cm deep) is transferred from the excavation part to the bulk part, then another 40 cm of the loosened most fertile layer remains on the former .

The same thing happens as a result of self-terracing on a slope where no terraces are built. The only difference is that, since the row spacing here is narrower than the terrace fabric (3 m instead of 4), the slope during self-terracing is slightly lower in height.

The overwhelming majority of researchers in our country and abroad believe that when cultivating grapes, slopes should be terraced already at a steepness of 10-12º, and in some cases even less steep.

Terraces are built by removing soil from the upper part of the strip allocated for the terrace and moving it to the lower part. In a section by a vertical plane perpendicular to the canvas, the excavation and fill parts have the shape of irregular triangles, the areas of which must be equal (Fig. 84).

A number of design and research organizations are developing special machines for the construction of terraces equipped with active working parts. In the coming years, the industry will produce such machines. Currently, terraces are constructed using commercial earthmoving and other machines equipped with simple devices. Science and practice have developed several methods for the mechanized construction of excavation-fill terraces. These methods are as follows.

Cultivated terracing is applicable on slopes up to 16º steep. A general purpose plow is used to repeatedly pass along the slope strip allocated for the terrace. They plow with the formation turning down the slope. The soil from the excavation part of the roadbed gradually moves down, forming the bulk part of the roadbed and a slope. The number of plow passes depends on the steepness of the slope and the width of the blade. This method can be used when the development of a slope area is planned for many years. Then, in the first years, the strips plowed under the terraces are occupied with grain or row crops, cultivated according to the strip farming system. When the process of terrace formation is completed, perennial plantings are planted on them. The disadvantages of tilled terracing include the limited steepness of the slope where it can be used, and the insufficient depth of the loosened layer in the excavation part of the canvas.

Bulldozer terracing on gentle and steep slopes. The construction of terraces using this method means that using a universal bulldozer or a passive terracer, the soil is cut off from the upper (along the slope) part of the strip allocated for the terrace and pushed onto its lower part. As a result, a canvas of the required width is formed. The bulldozer method of terracing is less productive than plowing and planting. The excavation part of the canvas is not loosened at all and the top fertile layer of soil is cut off and transferred to the bulk part and slope. Such terraces are in greater need of soil cultivation work.

Plantation terracing. The strip of slope allocated for the terrace is plowed with a planting plow with the layer turning down the slope. As a result of plowing and subsequent leveling of the strip with a grader or disc harrows, a well-loosened surface is formed. The humus layer of soil is distributed evenly over the canvas. Labor productivity during plantation terracing is high. The disadvantage of this method is its limited applicability, since the tractor unit cannot operate effectively on slopes greater than 18°.

With all methods of constructing terraces, the excavation slope is cut off using a grader or special devices, the surface is leveled, loosened and fertilized.

Construction cannot be considered complete if the roads and turning lanes provided for by the project are not constructed. The terraced plot is accepted by the commission.

A special feature of planting grapes on terraces is the need to strictly observe the mutual parallelism of the rows and the designed distances from the outer rows to the slopes. These conditions on terraces must be met with greater care than on plains, otherwise special tillage machines cannot be used.

Since grapes of weak and medium-growing varieties are planted on terraces, the row spacing here is 2 or 2.25 m, and the distance between plants in a row is from 1 to 1.5 m. This planting scheme makes it possible to have from 2.5 to 3 m per hectare. .5 thousand bushes. To ensure maneuvering of tractor units, the turning radius of terraces and rows must be at least 15 m, and the width of roads and turning lanes must be 7-8 m.

Add a comment

JComments

Summer kitchen and dining area

There is a recess in the slope for the kitchen, so this area looks like a natural extension of the landscape. The kitchen is quite austere, but functional: there is a sink, a small work surface and a pizza oven. What more do you need for a family Italian feast in the backyard?

It is worth paying attention to the unusual teardrop-shaped table. This design move avoids the feeling of bulkiness. The whole project looks easy, dynamic, stylish.

An interesting detail is the mobile “roof” over the dining area. In order not to burden the space with complex architectural forms and to give the owners the opportunity to let the sun into the yard or, conversely, to hide from it, the designers proposed using thick fabric secured to three thick ropes instead of flooring.

This roof can be easily removed or washed if necessary.

Plants on the terrace: garden in a pot

Small gardens, ideal places for potted plants, can be set up and rearranged to suit your taste and thus change existing concepts by introducing new color and decoration.

It is better to plant seasonal plants in pots, for example, spring ones (hyacinths, tulips and colorful pansies) - they bloom beautifully when the garden is still in sleep mode, and there are no leaves on the trees yet, but after flowering they are yellow and not very decorative.

Then they can be replaced by long-blooming petunias, geraniums or decorative begonias from mid-May to the end of summer. In autumn, their place in pots will be taken by multi-colored chrysanthemums, heathers and bloody heathers.

The garden should look decorative at any time of the year, so plants with a long flowering period are desirable, and plants with evergreen leaves, which create an ideal background for flowers, and most importantly - are attractive all year round. This is important so that the garden does not look deserted during the winter months.

To avoid monotony, it is worth using plants that differ in shape and color, but it is better to be guided by the principle of similarity than by contrast. You should not introduce too many species so as not to create the impression of excessive diversity. Instead, it is better to plant groups of different varieties that are similar to each other and slightly different in color or size.

Landings

Apparently, the owners of the house are not big fans of gardening and gardening. The landscape design of the garden is minimalist. The main dominants here are trees. The rest of the space is sown with a neat lawn.

Along one wall from the entrance of the house to the kitchen there is a green misk border with low shrubs and ground cover plants. At the entrance to the kitchen you can see pots of ficus and tangerine.

Of course, if desired, the tiers could be used as raised beds, or a few vertical beds could be added, but it would be a completely different garden with a different character and atmosphere.

Everything in this project is simple, natural, close to nature. It feels like you are in a green amphitheater. Moreover, maintaining the “marketable” appearance of such a garden is not difficult - just water it regularly and mow the lawn. Agree, it’s a dream, not a garden!

Need more inspiration for your landscaping makeover? Take a look at our article about the transformation of one site in Kyiv. The before and after photos will surprise you!

Based on materials from nicolaspinetto.com

Terrace flooring: the skeleton of a small garden

Sidewalks, paths and raised walls should form the basis of the entire design around which the rest of the garden is organized. Skillfully selected paving stones or stone slabs highlight the architecture of the building. We can easily find smooth, textured or distressed cubes, and having a variety of colors and shapes gives plenty of options for any arrangement.

In small gardens, natural and muted tones of the sidewalk are suitable, which harmonize perfectly with the vegetation. It is better to choose bright colors that illuminate and expand small spaces.

In addition, stone walls and raised discounts help create a unique climate by dividing the garden into zones and highlighting the natural benefits of greenery. At the same time, they emphasize various elements, and most importantly, they visually enlarge the garden. It is enough to lower the area by ten centimeters to make the garden seem larger.

Raised discounts and paths represent frames that separate the plant area from the useful one - they are functional and decorative at the same time. In order for the terrace to turn into a garden, you need to skillfully combine “hard” and untreated surfaces of delicate and soft greenery, so that concrete or stone does not dominate the composition, and at the same time emphasize the beauty of the planted plants.

Small urban gardens, surrounded by walls of buildings and surrounding areas, appear smaller than they really are. To visually enlarge them, divide the garden into smaller zones and leave one of them open. Also keep in mind that slight differences in height and rounded paths will visually increase its surface area.